A meeting place with Medieval origins

The Bremhill village cross is a well-preserved example of a standing cross which has stood in the centre of the village for many centuries. The considerable wear on the steps is testament to the importance of the cross over these years. The original purpose of the Medieval Cross is unknown but several religious orders and activists have used it as a vantage point to preach from its steps.

Standing crosses served a variety of functions. In church-yards they served as stations for outdoor processions, particularly in the observance of Palm Sunday. Elsewhere, standing crosses were used within settlements as places for preaching, public proclamation and penance, as well as defining rights of sanctuary. Standing crosses were also employed to mark boundaries between parishes, property, or settlements. Some crosses were linked to particular saints, whose support and protection their presence would have helped to invoke. Crosses in marketplaces may have helped to validate transactions. After the Reformation, some crosses continued in use as foci for municipal or borough ceremonies, for example as places for official proclamations and announcements; some were the scenes of games or recreational activity.

One particular event held here at the Bremhill Cross was of such historical importance that it was picked up in the National press and perhaps helped shape the course of history. On Tuesday 3rd February 1846 a farm workers demonstration took place. The Observer reported that “it was no ordinary meeting. Women spoke as well as men!” The article goes on to describe the scene:

“In the centre of the open space... close to the stone cross... a group of peasantry-men, women and children (around 1,000). Every moment fresh parties arrived from different farms. Some of them had trudged ten or twelve miles, and this after a hard day's work in the fields. ... appearing from the narrow streets-gliding across the churchyard... The men appeared gaunt, raw-boned set-the women pinched and care-worn”

However, the most influential account was probably that of the Morning Chronicle, whose journalist wrote ‘the meeting originated entirely with the working men’ and they were brought together by their collective ‘hunger.’

“He pointed out, ‘every influence was brought to bear, first to prevent (the meeting) from taking place and second to keep the labourers from attending.’ This influence included the local clergyman, Reverend Henry Drury, who had taken legal advice to see if the villagers could be prevented from attending. When that failed, he managed to get ‘a great number of constables in private clothes’ to participate in the gathering in order to disperse the crowd at the first sign of trouble (in the event they were not needed). Rev. Drury also told the man putting up handbills to advertise the meeting, that he would be ejected not merely from his job but from ‘the country’ if he continued.

Despite this, and attempts by local farmers to stop the attendance of local people, ‘they refused to a man; and to a man attended.’ Sometime between seven and eight, the proceedings began. The chairman of the meeting was Job Gingell, a local labourer, who sat on one of the cross’s stone steps. In his hands, he held a flickering candle and called the meeting to order.

‘Around the cross, the people clustered, forming a dense impenetrable mass.’ The three reporters sat to one side, in a make-shift tent which had been created using stakes cut from the hedge and canvas stretched over the resultant frame. The Chronicle painted a picture of the unsophisticated labourers, ‘who knew nothing of the rules of such assemblages,’ but who instead spoke sharing their own stories, ‘their own history of slow starvation.’ The meeting did not have an overtly political agenda even if the Anti-Corn Law League had helped to set it up. Instead, the labourers and their wives quietly shared their accounts, which exposed the harsh and difficult nature of their daily struggles. Towards the end of the meeting, a middle-aged woman in a long grey coat and old bonnet rose to speak, and by the illumination from Job Gingell’s candle, she partly read, partly recited her speech. This was Lucy Simpkins. Her family were based in Charlcutt and she was living at Hilmarton at the time.

Her speech was long and passionate. “Don’t you think we have a great need to cry to our God, to put in the hearts of our gracious Queen and her Members of Parliament, to grant us free trade, that a poor father and mother may sit down with a great loaf, and give their children a good meal of bread a long time which they have been strangers to.”

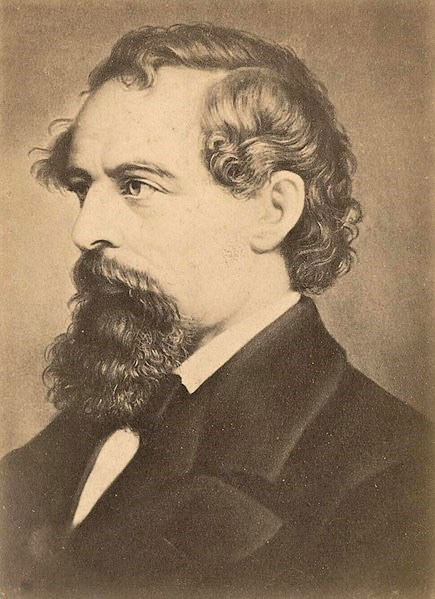

It ended with loud cheers from the assembly. The accounts of the meeting began to be published in the press on 12 February. In London, a new liberal and resolutely Anti-Corn Law paper, the Daily News, had just gone into production the previous month, under the editorship of author Charles Dickens. The Daily News published their account of the Bremhill meeting on 13 February. And with lightning speed Dickens published his poem, Hymn of the Wiltshire Labourers, inspired by the event in Bremhill and particularly by Lucy Simpkins' speech the very next day. It was designed to ‘elicit sympathy for the people and the repeal of the Corn Laws.’ In it, he portrayed ‘a landscape fraught with exploitation and social inequalities, embedded with myth and corrupted by religious, political and economic greed and ambition’ which ignored the well-being of ordinary citizens.

So what of the aftermath and the influence of these events? The participation of some local farm labourers had repercussions - farmer Stephen Stiles Jeffreys of Spirthill sacked five of his workers who had attended the meeting. References to the meeting at Bremhill would find their way into the parliamentary debate on the topic of the Corn Laws. Allusions in the press also continued for much of the rest of the month. Suffice to say, nationally, critical mass may have already been achieved in favour of the abolition of the Corn Laws, particularly as the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, was in support of it by the beginning of 1846. The issue was deeply contentious, and Peel was only able to get it through Parliament, later in the year, with the help of the opposition. It would split the Conservative Party.

As you stand here, perhaps you can hear the words of Lucy echoing on the wind.

Historic England Listing

Medieval village cross 100m north east of St Martin's Church

- Heritage Category: Scheduled Monument

- List Entry Number: 1019506

- View Historic England Listing